This series looks at the physicochemical challenges of PROTAC compounds. It explains how polymorph screening, salt/cocrystal optimization, and formulation and dosage-form development can improve solubility, stability, and bioavailability. The goal is to offer practical solutions for problems encountered during PROTAC R&D.

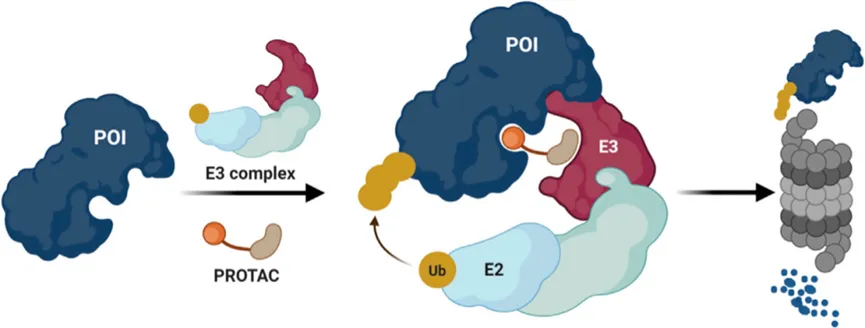

PROTACs (proteolysis-targeting chimeras) are an emerging targeted protein degradation technology. Instead of inhibiting the target protein, they induce its degradation. Compared with traditional small molecules, PROTACs can address a wider range of targets, including those previously considered undruggable. They can overcome the problem of acquired drug resistance seen in some small-molecule drugs and provide prolonged duration of action. PROTACs often achieve potent degradation activity at low doses and demonstrate a favorable efficacy and safety profile. Their unique mechanism also allows for high functional selectivity, opening new therapeutic paths for challenging targets.

Figure 1. Schematic of the PROTAC mechanism involving E2 (Ub-conjugating enzyme) and E3 (E3 ligase/substrate adaptor protein)

Despite their promise, PROTACs face multiple development challenges. They typically have high molecular weight (MW > 700), high polarity, and poor solubility, which lead to low bioavailability. During CMC development phases such as solid-form (polymorph and salt/cocrystal) work, preformulation, and formulation, it is crucial to focus on improving these properties.

This first article of the series focuses on the physicochemical issues of PROTACs. It discusses how polymorph screening and salt/cocrystal optimization can improve solubility, stability, and developability.

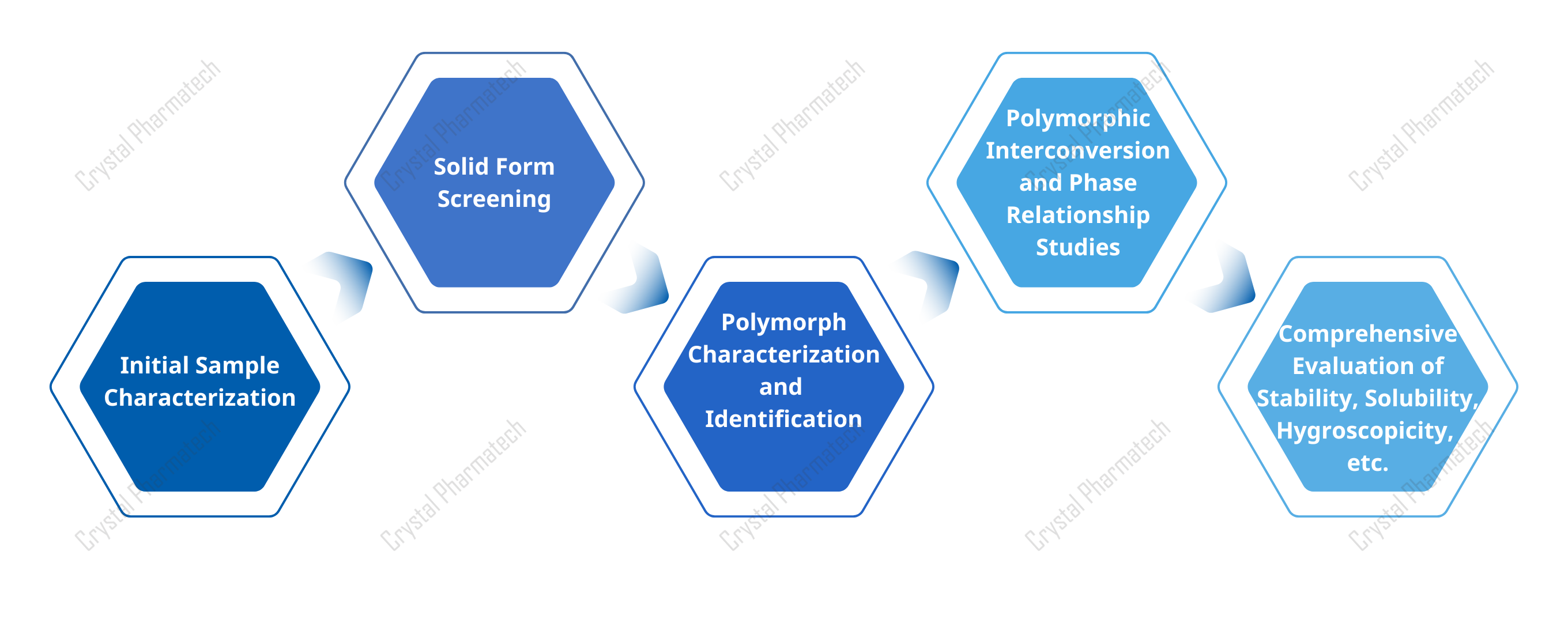

Most PROTAC starting materials are amorphous or have low crystallinity. Improving purity and stability of the free form is critical.

In designing a polymorph screening plan, scientists first characterize the compound’s physicochemical properties. Once its crystallization behavior is preliminarily understood, they conduct a systematic screening that accounts for both thermodynamic and kinetic factors.

Figure 2. Design of a Polymorph Study Plan

Figure 2. Design of a Polymorph Study Plan

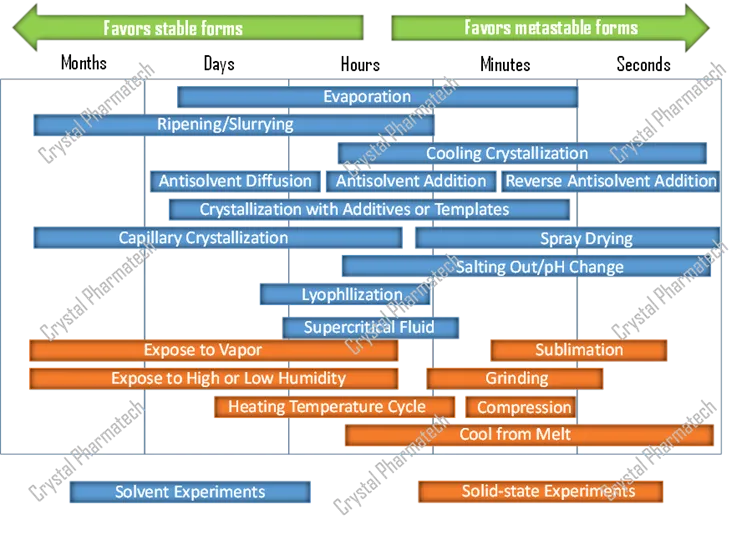

Common methods include solvent-mediated crystallization, thermal treatment, mechanochemistry, and solid-state transformations. The most productive approach is solvent-mediated crystallization, such as evaporation, cooling, antisolvent addition, and slurry stir. Solvent and temperature are the key factors. Use multiple temperatures and solvent systems. Slow crystallization tends to reveal thermodynamically stable forms. Fast crystallization often yields metastable forms.

Crystallization reflects competition between thermodynamics and kinetics. Uncontrolled crystallization times can range from seconds to years.

Figure 3. “Sample generation” methods and the time scales they favor

Mapping interconversion among forms is essential. For anhydrous forms, use the Burger–Ramberger rule, Van’t Hoff plots, and suspension competition to judge relative stability. For hydrates, stability depends on water activity; sorption/desorption isotherms and water-activity suspension tests help define stable regions. Solvates are used less often as drug forms. They can serve as intermediates for purification or as transition forms to access difficult targets.

Complete the screen by evaluating properties such as solubility, hygroscopicity, and stability. Choose the most suitable form for further development.

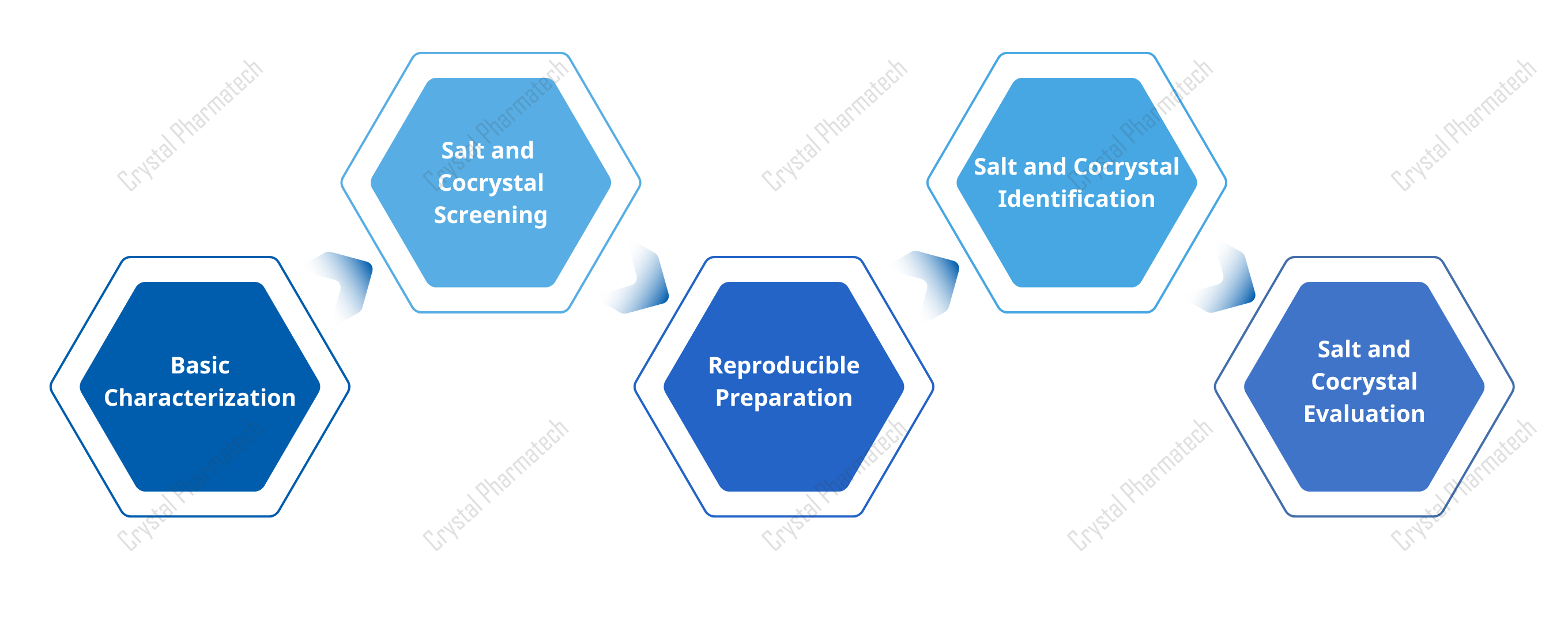

PROTACs often contain ionizable groups (e.g., amines, carboxylates). Salt formation or cocrystallization is therefore an important development strategy. It can:

· Improve solubility and bioavailability and increase developability.

· Improve patient compliance and enhance stability.

· Strengthen or work around intellectual property.

Figure 4. Workflow for salt/cocrystal development from screen to evaluation.

Figure 4. Workflow for salt/cocrystal development from screen to evaluation.

Design considerations:

· Counterion/coformer. Select counterions based on the structure and properties of the free form, considering pKa, structure, molecular weight, and safety. For cocrystals, coformers can be synthetic fragments; consider hydrogen-bonding and solubility. As a rule of thumb, if ΔpKa (free form vs. counterion) > 2, salt formation is likely; if ΔpKa < 2, cocrystal formation is more likely.

· Solvent system. Choose according to solubility. Use multiple systems, including aqueous, to survey polymorphism in potential salts/cocrystals. Monitor stability of both free form and counterion/coformer in solution.

· Crystallization process. For salts, common methods include reaction crystallization, cooling, evaporation, and antisolvent addition; combinations are common. For cocrystals, use reaction crystallization as well as grinding, melt methods, and ultrasonic slurry. Run the work in two stages: “screen” to identify candidates using efficient characterization, then “select” to scale promising ones and perform full evaluation (often focusing on solubility and stability). Because salts/cocrystals can also be polymorphic, perform a polymorph screen on the chosen salt/cocrystal to find the best solid form.

Background

Candidate A had MW ~850–900 Da and pKa 5 (weak acid). The starting sample was amorphous. Prior column purification was time-consuming and only partly effective; the amorphous sample reached ~85 area% purity. The team sought a solid form with improved properties for downstream development.

Study Plan

Start from the amorphous material and run polymorph and salt screens in parallel.

· Polymorph screen: Fifty experiments using different methods produced a low-crystallinity free acid, Form A. Purity increased notably.

· Salt screen: Thirteen counterions across five solvent systems (65 experiments) generated amorphous salts.

· Optimization: Scale up and increase crystallinity of free acid Form A. Process optimization significantly improved crystallinity.

· Evaluation: Form A showed favorable solid-state stability, solubility, and hygroscopicity. It was recommended for further development.

In the first round, most samples were amorphous or oily/gel-like. Only a weakly crystalline free acid Form A was obtained. In the second round, the team used Form A as the seed and adjusted design and parameters. By tuning solvent and cycling temperature, they obtained a highly crystalline anhydrous form with markedly improved purity.

Background

Candidate B had MW ~870–900 Da and pKa 10. The starting sample had low crystallinity. The goal was a systematic salt study to obtain a high-solubility crystalline salt for development.

Study Plan

Characterize the starting sample. Choose counterions and solvent systems based on pKa and solubility.

· Salt screen: Twenty counterions across three solvent systems (60 experiments) yielded 12 crystalline salts, which were characterized.

· Scale-up and characterization: Three salts with the most suitable properties were scaled up and characterized by XRPD, TGA, DSC, NMR, and molar ratio.

· Evaluation: These three salts were assessed for solid-state stability, solubility, and hygroscopicity. The maleate salt showed a marked solubility increase and favorable solid-state stability. It was recommended for further development.

· Maleate polymorph screen: One hundred experiments using various methods produced two maleate polymorphs. Maleate polymorph A was recommended.

Maleate polymorph A showed ~100-fold higher solubility than the free form, which greatly improved solubility and bioavailability. The solid-form landscape was simple. Polymorph A was thermodynamically stable. Selecting maleate polymorph A enables a conventional solid oral dosage form and lowers development cost.

1. Nalawansha DA, Crews CM. Cell Chem Biol. 2020;27(8):998–1014.

2. Anderton, Amer. Pharm. Rev. 2007, 10, 34–40.

Subscribe to be the first to get the updates!